The period of European history sometimes called the Viking Age is generally considered to run from the last years of the eighth century to the end of the eleventh century. Its beginning and ending dates are determined, in the eyes of most historians, by the beginning and end of a prolonged period of Viking raids — the actions for which the Scandinavian peoples of this era are best known.

The earliest account of a Viking attack is found in the Saxon Chronicle, a running summary of English history from the year 1 A.D. to 1154 A.D. [1] According to the Chronicle, in the year 787 A.D. [2] three ships of Northmen came ashore near Portsmouth in England. In the words of the chroniclers:

The reeve [the king’s sheriff, or steward, for the local shire] then rode thereto, and would drive them to the king’s town, for he knew not what they were; and there was he slain. These were the first ships of the Danish men that sought the land of the English nation. [3]

Additional attacks followed in quick succession. In 793 Viking raiders sacked the monastery of Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumbria in northern England, and in 794 they ‘spread devastation among the Northumbrians’ [4] and sacked another monastery located near the mouth of the Wear River. By the early decades of the ninth century, Viking raids had become a frequent occurrence not only in England, but also in Ireland and the lands of the Franks on the European mainland.

The Vikings’ attacks continued off and on for three hundred years. The nature of the attacks changed over time, however. At first the raids were relatively small in scale, such as the initially recorded assault by three ships in 787. The targets of these early attacks were frequently Christian monasteries and churches, for the simple reason that these religious centers represented concentrations of wealth that were poorly, if at all, protected. By the mid ninth century, however, the Viking raids had begun to take an ominous turn. More and more often they were perpetrated by large fleets of Viking ships, and the raids — which by this time often involved the sack of fortified towns –came to bear more resemblance to invasions, and acts of war, than hit and run piracy.

From reading the accounts by religious chroniclers in England and Frankia — the primary source of contemporary descriptions of the Vikings’ incursions — it is easy to come away with the impression that Viking raids were invariably attacks of ruthless, barbaric savagery that left only dead bodies and smoking ruins behind. The reality must often have been considerably less severe, however, for the Vikings tended to attack the same towns repeatedly, year after year. The Frankish trading center of Dorestad, for example, located a short distance from the coast along the Rhine River, was sacked four times between 834 and 837, and the Frankish towns of Quentovic and Rouen — known as Ruda by the Northmen — were also repeatedly sacked. Even Paris was taken more than once. Obviously, even after the earlier Viking assaults on these towns, enough of value remained not only to entice successive attacks, but also to cause the towns’ populations to continue living there. Indeed, particularly where the Church was involved, it was a common practice for the raiders to merely capture monasteries and members of religious communities, then extract a ransom in exchange for releasing their captives unharmed, and leaving the buildings undamaged. Nevertheless, the raids took a toll. Over time, many monasteries near the coast in England and Frankia were abandoned, and several coastal regions of Frankia, including Aquitaine, saw significant reductions in population as their inhabitants moved inland to safer locations.

Beginning in 865, a major influx of Vikings, called the ‘Great Army’ in the Saxon Chronicle, began systematically warring against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England. No longer did the Vikings retreat to their own land at the end of each raiding season. They wintered over in England, equipped their army with horses, and attacked in a series of fast moving campaigns launched by land as well as by sea. Over a fifteen year period of almost constant warfare, the Saxon kingdoms of Kent, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria were effectively destroyed [5]. Only the West Saxons, under the leadership of Alfred the Great, were able to successfully resist the Great Army, and preserve Wessex as an independent Saxon kingdom.

Many members of the Great Army settled on the lands of the Saxon kingdoms they’d overrun, and the eastern region of England became known as the Danelaw, an area where the laws, customs, and even place names of the Viking inhabitants largely replaced those of the conquered Saxons. In the north of England, the former Saxon kingdom of Northumbria became an independent Viking kingdom, and the town of York — which was known as Jorvik while under Viking rule — became a bustling center of trade, with a population of nearly ten thousand by the year 1,000 A.D. Major Viking enclaves were also founded in Ireland at Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, and Limerick, and Viking settlements were established off the coast of Scotland among the Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland Islands.

Not all of the members of the Great Army chose to settle on the lands they’d won in England. In 880, remnants of the Great Army — still a formidable force — crossed the channel, and harried the Franks for many years. The Franks tried, with limited success, to reduce the Vikings’ ability to penetrate inland by building fortified bridges across some of their major rivers. Encouraging some of the raiders to make peace, fight for the Franks against their former comrades, and even settle on Frankish lands proved a more successful tactic, however. Some regions of Frankia ultimately won long-lasting protection by ceding coastal lands to the invaders. In the latter ninth century portions of Frisia were granted to two Viking leaders in exchange for their aid in repelling other raiders, and in the early tenth century the Frankish King Charles the Simple entered into a treaty with Rollo [6], a Viking leader, and granted him the lands around the mouth of the Seine River — which eventually became known as Normandy, after the Northmen who settled there — in exchange for Rollo becoming a Christian, swearing allegiance to Charles, and preventing other Viking raiders from penetrating the Frankish heartland along the Seine.

One aspect of Viking armies that made them such formidable foes was their mobility. Their swift, shallow-draft ships allowed them to move their armies quickly, and thereby to effectively apply the military doctrine of concentration of force against the slower reacting defenders of England, Ireland and Frankia. Even on land, Viking armies often continued to apply the strategy of speed in their campaigns. For example, although they did not fight on horseback as cavalry, the Vikings’ Great Army often deployed as mobile infantry, using captured horses to travel swiftly across country. And on those occasions when the Vikings did experience defeat, the mobility of their armies often allowed them to retreat from danger and avoid complete destruction.

Ironically, this advantage of mobility enjoyed by the Vikings was lost once they settled the lands they had captured, and created new homelands close to their enemies which could not readily be abandoned. The tenth century saw many of the Vikings’ successes of the ninth century reversed. During the early decades of the tenth century the Danelaw, which had become an independent Viking enclave in England, was forced to submit to and become part of the English kingdom of Wessex, and in 954 the English regained control of York, bringing an end to the Viking kingdom of Jorvik. In Ireland, the power of the Vikings as an independent force declined over the course of the tenth century until, at the battle of Clontarf in 1014, the Vikings of Dublin — the last independent Viking kingdom in Ireland — were decisively defeated by a coalition of forces led by Irish King Brian Boru.

In Frankia, the process of ‘defeating’ the Vikings who settled was more subtly achieved. The original land grant given to Rollo in 912 was added to on two occasions, more than doubling the size of Normandy, and at least one additional wave of Vikings settled there in the mid-tenth century. However, over time the Scandinavian settlers adopted the customs and language of the more numerous Frankish residents of the land, and by the mid-eleventh century the Normans were much more akin to Franks than to their Viking forebears.

The eleventh century brought a resurgence of Viking raids against England. Many of these were small scale affairs, much like the pirate raids of the early ninth century. The Viking settlers on the islands off the north and west coast of Scotland were the primary perpetrators of most of these acts of piracy against the coastal regions of Ireland and western England, that continued sporadically through most of the twelfth century.

Eastern England suffered from a different type of Viking predation during the late tenth and the first half of the eleventh century. In Scandinavia, the tenth century was marked by the development of strong centralized kingdoms in each of the Viking homelands [7]. However, regular taxation of the citizenry, as a method of raising revenue for the king, had not yet become a fully developed or well accepted concept in these relatively new kingdoms, whose citizens frequently became restive at efforts by their kings to control them. Viking kings of the eleventh century — and in some cases powerful independent Viking warlords who aspired to kingship — saw large scale attacks on the rich and now united kingdom of England as a convenient method of acquiring wealth, either through plunder or by exacting tribute from the English kings. On numerous occasions during the late tenth and early eleventh centuries marauding Viking armies were paid vast sums of Danegeld to leave England’s shores.

King Svein Forkbeard of the Danes was one of the most persistent Viking attackers of England during this period, and in 1013 he took his assaults on that land to a new level by conquering the country and forcing it to accept him as its king. He died shortly afterwards, but his son Cnut reasserted the Danes’ control over England by 1016, and in 1019 assumed the kingship of Denmark as well. Cnut created a short-lived northern European empire by defeating King Olaf of Norway in 1028 and assuming rule over that country, also. England was by far the richest of the kingdoms Cnut ruled, though, and he spent most of the years until his death in 1035 in that land.

After Cnut’s death in 1035 his empire quickly fell apart. His son, Harthacnut, was accepted as king in Denmark, but Cnut’s brother Harald was chosen by the Anglo-Danish nobility of England to rule there, while the son of King Olaf reclaimed the crown of Norway from the Danes. By 1042 the last Danish ruler of England died, though, setting the stage for a final round of major Viking assaults against England.

Edward the Confessor, the surviving son of the English king who had been deposed by Cnut, had been living in exile in Normandy. In 1042 he returned to England and reasserted English rule over the kingdom. But Edward died without an heir in 1066, and three claimants –two of Viking blood — asserted that the English throne should be theirs: Harald Hardrada, the King of Norway and a renowned warrior, William, the Duke of Normandy and a descendant of the Vikings who settled there, and Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex. When the Anglo-Danish nobility of England chose Harold as their king, the other two contenders began preparations to invade England.

The Viking army led by Harald Hardrada reached England first, though only by a matter of days. Landing in the north of England, an area whose population had a strong Viking heritage, he quickly captured the town of York and sought to raise allies among the local populace. The English army, led by Harold Godwinson, quickly marched to meet him, however, and won a devastating victory in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, slaying Norway’s king and much of his army in the process.

While the English army was in the north, the Norman army led by William landed in the south. The English forces rushed south to meet him, and at the hard-fought Battle of Hastings in September of 1066 were decisively defeated. Harold Godwinson was killed in the battle, and after a several month long campaign William was finally accepted as King of England by the English nobles.

Many historians consider the Norman conquest of England in 1066 to mark the end of the Viking Age. Sporadic Viking attacks continued well into the next century, however. In 1069, and again in 1075, large Danish fleets attacked England in the north, in support of uprisings against the Normans by the Anglo-Danish inhabitants of that region. In the last years of the eleventh century and first years of the twelfth, King Magnus Barelegs of Norway led expeditions against the Isle of Man, Wales, and Ireland. And Svein Asleiffarson, a Viking chieftain living in the Orkney islands, plagued Ireland, Wales and the Hebrides Islands, and was the terror of seafarers on the Irish Sea between England and Ireland, for decades until he was killed in an attack on Dublin in 1171 [8].

Who were the Vikings and where did they come from? What motivated them to repeatedly attack the peoples and lands of northern Europe?

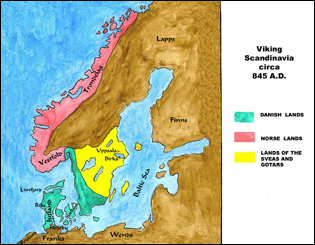

The Vikings’ homelands were those areas of Scandinavia which today comprise Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Although a common language was spoken across most of Viking Age Scandinavia — doubtless with some regional dialect variations — many of the peoples still tended to identify themselves according to ancient tribal divisions dating at least as far back as the period when the Roman Empire first encountered the Germanic peoples of northern Europe.

Norway was inhabited by peoples known as the Norse, and in the early Viking Age was ruled by a number of small local kings and chieftains about whom little is known. The history of Norway during the Viking Age was largely shaped by the efforts of successive rulers to consolidate power, eliminate rivals, and shape Norway into a single, unified kingdom.

Most of the peoples inhabiting the lands comprising the central and western portions of modern-day Sweden would have considered themselves either Gotars or Sveas, and it was not until near the end of the Viking Age when those two peoples became completely united under a single king. Although some Swedish Vikings are known to have participated in raids against the European countries lying to the west, they played a much more significant role in the east. Vikings from Sweden, known as Rus by the Slavic peoples whose lands they settled in, founded the Kingdom of Russia in Kiev and Novgorod, and by as early as 830 had established routes running south along Russia’s rivers that provided regular, direct trade between the Viking lands and the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople, and even the Arab kingdoms beyond.

Although their lands had originally been inhabited by several distinct Germanic tribes — the Danish mainland, Jutland, still bears the name of the Jutes who lived there — by the beginning of the Viking Age the peoples inhabiting what today comprises Denmark had the most highly developed central kingship of any of the Viking peoples, and considered themselves all to be Danes. Indeed, during the early Viking Age the Kingdom of the Danes consisted not only of the mainland and islands comprising modern day Denmark, but also extended over some of the lands of southern Norway and a large region of western Sweden. The map below illustrates the areas of Scandinavia which would have been considered the lands of the Danes, Norse, Gotars and Sveas in the mid-ninth century — the period when the Strongbow Saga begins.

Historians debate the causes behind the waves of Viking attacks on their neighbors to the south and west. Surely, though, the primary motivation for the Vikings’ raids is demonstrated by what the raiders sought. Back in their homelands, Viking warriors were, for the most part, farmers, and the supply of arable land was limited by the terrain of Scandinavia — a particular problem as the population of the Viking homelands increased over time. There was little opportunity for a man to better himself or to seek a fortune at home on the farms of Scandinavia. The Vikings engaged in piracy, and raided the lands of their neighbors, because they wished to better themselves. They sought to increase their wealth through plunder, through taking captives and exchanging them for ransom or selling them as slaves, or through — as in the Danelaw in England or Normandy in Frankia — the acquisition of land.

It is important to view the Vikings’ actions in the context of their time and culture, rather than judging them by our own. The Germanic peoples had for centuries viewed raiding the lands of others and taking their possessions as a legitimate, respectable profession and means of acquiring wealth. Beginning during the latter half of the third century A.D., and continuing off and on until the collapse of the Roman Empire, Germanic tribes drawn by the wealth accumulated by the Romans repeatedly pierced the Empire’s border along the Rhine and Danube Rivers and raided deep into the Empire’s lands. The Vikings’ extortion of Danegeld from the Franks and English differs little from the Visigoths extracting from the city of Rome in the early fifth century a ransom of five thousand pounds of gold, ten thousand pounds of silver, and three thousand pounds of pepper in exchange for not sacking the city.

Eventually many of the Germanic raiders who attacked the Roman Empire did the same thing the Vikings did, centuries later: they captured lands, settled on them, and over time blended with the local population. The Franks, originally a pagan Germanic tribe who committed years of hit and run raids into Gaul, eventually conquered that area of the Empire, settled there, and over time adopted the culture, religion, and even language of the provincial Roman citizenry whom they ruled and intermarried with. In England, after the Roman legions were withdrawn to face growing threats in other parts of the Empire, the Romanized Britons invited Germanic warriors to come fight as mercenaries for them. Realizing how defenseless and rich a prize Roman Briton was, the mercenaries rebelled, and brought more of their kind from the continent. Eventually these fifth century Germanic invaders, composed primarily of Saxons, Angles, and Jutes, conquered most of Britain and established the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that would, several centuries later, become the prey of a new wave of Germanic invaders: the Vikings.

It was characteristic of the Vikings, when they settled in foreign lands, to be open to the peoples already there, and to their cultures. Thus, although during the Viking Age many large Viking enclaves existed outside of Scandinavia, including in Ireland, in the north and east of England, along the coast of Frankia in Normandy, and to the east in Russia, over time the Vikings who settled there intermarried with and were absorbed into the local populations. Thus many who are of northern European descent may bear some trace of Viking heritage in their distant ancestry, and many of the Vikings’ contributions to the peoples and cultures they blended with are no longer readily attributable to their true source.

The Vikings had very strong beliefs in honor and in personal freedom. Indeed, many of the early Viking settlers of Iceland fled there from Norway, because they were unwilling to accept the losses of personal freedom that Norway’s kings were imposing on the citizens of that land, in their efforts to consolidate their power and to force an often resistant pagan populace to accept the Christian religion.

The Vikings also had a very strong belief in the law, and expected — sometimes in vain — that even their kings should obey and be bound by their laws. Every district held periodic regional assemblies, called Things, where disputes, whether civil or criminal, could be brought for peaceful resolution according to law. Although most, if not all Vikings would have considered themselves bound by ties of allegiance and loyalty to some figure of authority, whether a local chieftain, a regional overlord such as a Jarl, or a king, and although slavery was an accepted feature of Viking society, still they had a very strong tradition of a free class of common men. Ironically, many of what today are thought of as centuries-old English traditions such as the rule of law, and the free yeoman class that existed in medieval English society between the serfs and the nobility, are more likely traceable back to the predominately Danish Vikings who conquered much of England in the late ninth century, and brought their beliefs, culture and traditions to that land when they settled there.

Other contributions by the Vikings are less abstract. They were not only warriors, pirates, and raiders. The Vikings were fearless explorers, and vigorously involved in trade. The exploration of the rivers of Russia by Swedish Vikings led not only to the creation of a kingdom there that was the genesis of the Russian state, but also established a connection between northern Europe and the economies and cultures of the Eastern Roman Empire and the Arab world. Although much of their culture was rural and based on farming, the Vikings were also town builders, for they needed centralized trade centers to support their far flung trading networks. The city of Dublin in Ireland was established by the Vikings as a fortified base and trading center, and during the Viking Age the towns of Jorvik in northern England, Ribe and Hedeby in Denmark, and Birka in Sweden were also all vigorous commercial centers.

The period of history between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the growth, during the Middle Ages, of the European nations that endure to this day, was a time of great change. Through their roles as raiders, colonists, and traders in spreading exposure to different cultures and ideas across much of Europe, the Vikings played as essential role to this time of change as honeybees play to the process of fertilization and cross-pollination in agriculture. Without question, the world today would be a far different place without the numerous contributions of the Vikings.

The Ancient World, Richard Mansfield Haywood (David McKay Co. Inc., NY 1971)

A History of the Vikings, Gwyn Jones (Oxford University press, Second Edition 1984)

Encyclopaedia of the Viking Age, John Haywood (Thames & Hudson, NY & London 2000)

Heimskringla, or The Lives of the Norse Kings, Snorri Sturlason (Dover Publications, NY 1990; edited by Erling Monsen/trans. A.H. Smith)

Medieval Scandinavia: an Encyclopedia, Philip Pulsiano, editor (Garland Publishing, Inc., London 1993)

The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings, John Haywood (Penguin Putnam Inc., NY 1995)

The Saxon Chronicle, trans. Rev. J. Ingram (Studio Editions Ltd., London 1993)

The Viking World, James Graham-Campbell (Frances Lincoln Ltd., London 2001)

The Vikings, Else Roesdahl (Penguin Putnam Inc., NY 2nd Edition 1998)

The Vikings, Johannes Brondsted (Viking Penguin Inc., NY 1965)

[1] The various surviving manuscripts of the Saxon Chronicle were written by English clerics or monks, and maintained over the centuries by monasteries in England. Entries for the earliest centuries deal primarily with events that occurred away from England, and concern the early years of the Christian church and major political and military events of the Roman Empire. Although the exact dates when the earliest copies of the Chronicle were begun is not known, clearly the entries for the earliest centuries were not contemporaneous accounts, but presumably drew upon pre-existing sources. Significant blocks of years for which no entries at all were made occur in the Chronicle during the period from the beginning of the second century to the early decades of the fifth. Beginning in the mid fifth century, however, the frequency of entries picks up sharply, as the Chronicle begins to follow the history of the Saxons’ arrival in England, and the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms they founded there. By the late eighth century — the beginning of the Viking Age — entries are, for the most part, annual, and to all appearances were made contemporaneously or close in time to the events they describe.

[2] 789 A.D. according to some versions.

[3] The Saxon Chronicle, trans. Rev. J. Ingram (Studio Editions Ltd., London 1993), page 78.

[4] The Saxon Chronicle, page 81.

[5] Viking tradition identifies the original impetus for this sustained attack as revenge for the death of the legendary Viking leader Ragnar Logbrod at the hands of Aella, the king of Northumbria. According to this version of the Great Army’s initial assault on England, Ragnar’s sons raised a large force and led it against Northumbria, overrunning the countryside, capturing York, and killing Aella, then turned their army against the Saxon kingdoms to the south.

[6] Although known as Rollo to the Franks, he is identified in Viking sources as Rolf or Hrolf. Efforts to follow the careers of Viking leaders are often complicated by the tendency of the writers of the English, Frankish and Irish chronicles to identify the Vikings by their own interpretations or translations of the Vikings’ names.

[7] Although the Danes had been ruled by a single, central king since even before the Viking period, the lands comprising modern day Norway and Sweden were, at the beginning of the Viking period, divided into a number of small kingdoms that were in some cases based on old tribal divisions of the peoples living there.

[8] The known history of the Viking Age is largely defined by their attacks against England, Ireland, and Frankia. History, or more accurately the knowledge and study of history, depends on some evidence of events surviving until a later time, to provide a source from which scholars can determine the events of earlier ages. We know a great deal about the Vikings’ effects on the English, Irish, and Franks largely because Christian clerics in those lands maintained detailed written records which documented, among other things, the attacks by the Vikings.

![]() Without question, the Vikings also regularly attacked the Slavic peoples and lands along the southern and eastern coasts of the Baltic Sea, an area even closer to the Viking homelands than Frankia, England, or Ireland. Many Viking sagas mention raiding expeditions in these areas, though they provide little in the way of concrete dates and facts. However, because the Slavic peoples, who like the Vikings themselves were pagan during much of the early Viking Age, apparently did not maintain regular historical annals, relatively little is known about the extent of the Vikings’ attacks on this region, or the effect they played in its history.

Without question, the Vikings also regularly attacked the Slavic peoples and lands along the southern and eastern coasts of the Baltic Sea, an area even closer to the Viking homelands than Frankia, England, or Ireland. Many Viking sagas mention raiding expeditions in these areas, though they provide little in the way of concrete dates and facts. However, because the Slavic peoples, who like the Vikings themselves were pagan during much of the early Viking Age, apparently did not maintain regular historical annals, relatively little is known about the extent of the Vikings’ attacks on this region, or the effect they played in its history.