Halfdan Hroriksson, the young Dane who is the central character of the Strongbow Saga, is an archer. To what extent did the Vikings actually use archery, particularly in warfare? To answer that question, we can examine archeological evidence as well as contemporary accounts of Viking warfare.

Relatively few wooden items survive from the Viking era. Unless preserved by chance in an environment where little or no oxygen was present [1], wooden artifacts from earlier time periods tend to decay, leaving little archeological evidence for modern historians. Thus, although weapons were commonly buried with their owners in the graves of deceased pagan warriors during the Viking Age,[2] and numerous Viking burials contain metal arrowheads, suggesting that bows and arrows were probably interred in the grave, very few actual bows from the Viking Age have survived. However, a few archeological finds have been made of bows dating from the Viking era, as well as finds in Scandinavia that predate the Viking period. Taken together, they show not only that bows were in use by the Scandinavian peoples before and during the Viking Age, but also provide evidence of the types and power of the bows the Vikings used.

Remnants of bows dating as far back as the Stone Age have been found in Denmark, and bows made in the classic longbow shape and proportions, made of elm, have been found in Denmark and dated to the Bronze Age. One such longbow, found on the Danish island of Sjealand, has been dated to approximately 2800 BC. Another, found at Viborg on the central Jutland peninsula, has been dated to between 1,500 and 2,000 BC.

Prior to the Viking Age, Germanic tribes sometimes celebrated victories over foes by throwing their defeated enemies’ captured weapons and gear into lakes or bogs as an offering to their gods. One such offering — a ship filled with weapons and sunk in a bog as a votive offering to the gods, dating from the third century AD — was discovered at Nydam, near the southern end of the Jutland peninsula. The Nydam ship provided a particularly rich archeological find from a history of archery standpoint, for it contained a total of thirty-six partial and complete bows. Most were classically proportioned longbows, some over six feet long, made of different woods, including yew. The limbs of a few of the longbows were tipped with sharpened iron nocks, apparently to allow the bow to be used as a close range stabbing weapon if an enemy closed with the archer.

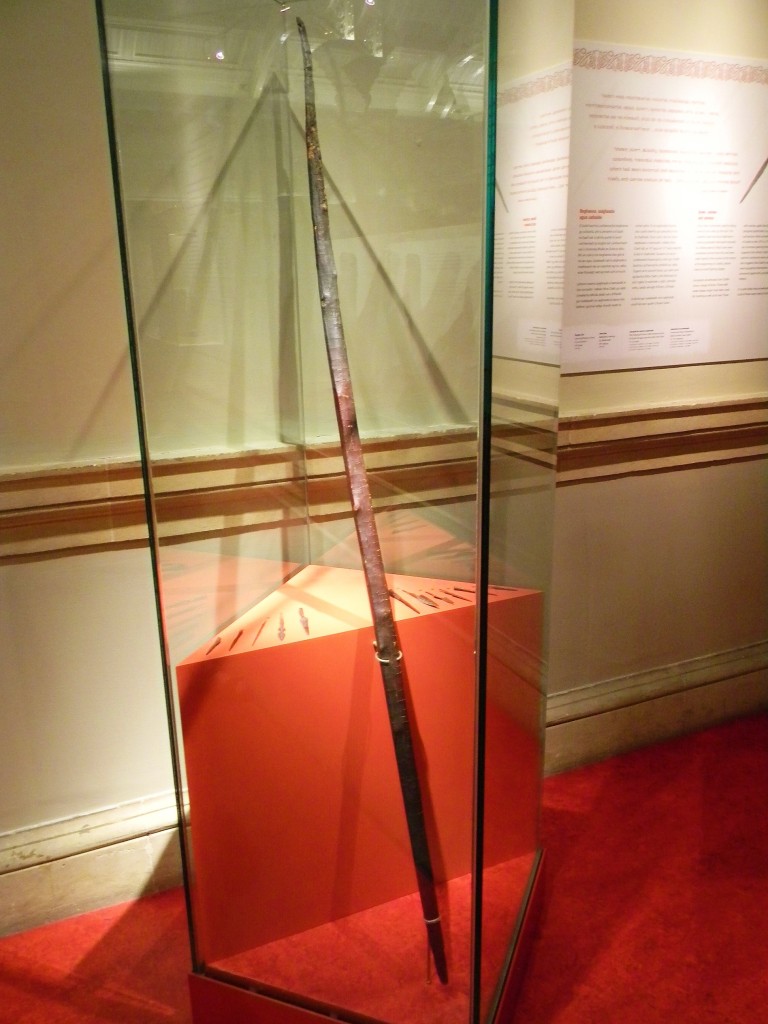

Two bows found in Viking era burials provide archeological evidence of the types of bows actually used by Viking warriors. Both are large, classically shaped and proportioned longbows made of yew. One, found at Ballinderry in Ireland, was six feet one inch long. The other, found in a burial at Hedeby in southern Denmark, was six feet three and one-half inches long. This latter bow was sufficiently well preserved to allow estimation, from its size and proportions, that its draw weight was probably around one hundred pounds — a powerful bow, indeed.

Viking era longbow on display in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.

Accounts of the Vikings’ use of bows in warfare, written during the Viking Age, also provide evidence of the Vikings’ use of archery. These contemporary accounts come from three main types of source material: written accounts of warfare with the Vikings by peoples who fought them, Scandinavian laws dating back to the Viking era, and the sagas, the Vikings’ own stories about their heroes and their history. [3]

Detailed contemporary Frankish descriptions exist of the year-long siege of Paris by Vikings during 885 and 886. During that protracted struggle, the Viking’s army was described by the Franks as not only using sophisticated siege techniques, such as employing mobile siege towers against the Franks’ fortifications, but also as raining heavy archery fire upon the defenders in support of their assaults against them.

Late Viking era laws from Norway and Sweden specified how free landowners were required to respond when summoned to a general muster of arms. In addition to bringing a spear, sword or axe, and a shield, each warrior was expected to be armed with a bow and arrows.

It is within the various sagas, though, that we find the most detailed descriptions of the Vikings’ use of archery.

When fighting on land, Viking armies typically fought on foot as infantry, in a close formation known as a shield wall. The Heimskringla, a thirteenth century compilation drawn from numerous earlier sagas about various kings of the Norse Vikings, or Norwegians, contains several descriptions of how archery was used in shield wall formations. For example, in the History of Saint Olav, who was born in 995 and ruled Norway from 1015 to 1030 AD, the attack of a Viking shield wall formation is described as follows:

“[T]hey who stood foremost struck blows, they who were next thrust with spears, and all who came up behind, shot with spears or arrows or cast stones or hand axes or javelins.” [4]

At the Battle of Stamford Bridge in northern England in 1066 AD, a Viking army led by Norwegian King Harald Hardrada was met by an English army composed of both infantry and cavalry. The Heimskringla gives a detailed account of how King Harald, a noted Viking war leader, arrayed his army to face the threat of cavalry charges. He arrayed his warriors in a shield wall that was “long and not thick,” and the King instructed that “they who stand foremost shall set their spear shafts in the earth and turn the points towards the riders’ breasts, in case they ride in upon us; and they who stand in the second rank shall set their spear points towards the horses’ breasts.” The bowmen in the army were arrayed behind, with the household warriors of the King and his ally, Tosti the Jarl, forming a mobile reserve. [5]

The volume of fire from arrows and thrown missiles during typical Viking battles was apparently great. The account of a battle in 961 AD between Danish and Norwegian Viking armies states “arrows and spears and all kinds of shooting weapons were flying as thickly as the snow drifts.”[6] The Norwegian’s king, Hacon the Good, was killed by an enemy arrow during the battle.

King Hacon was only one of several Viking era kings slain by enemy bow fire. Others include Danish King Harald Bluetooth, slain from ambush in the year 986 AD after a day of inconclusive battle at sea against his rebellious son, Svein Forkbeard. King Harald went ashore to warm himself at a fire after the battle, and one of Sveins’s supporters crept close through the surrounding woods and killed the Danish king with a well placed arrow. Norwegian King Harald Hardrada’s careful battle plans at the Battle of Stamford Bridge — described above — failed, and his army was decisively defeated, after he fell with an arrow through his throat, and only days later the English king who’d defeated him, Harold Godwinson, was defeated and slain at the battle of Hastings after being struck in the eye by an arrow shot by a Norman archer. [7]

Warfare at sea during the Viking Age depended heavily on missile fire. Viking ships were not designed for ramming, a style of naval warfare long favored in the Mediterranean. Instead, in ship to ship combat, the Vikings’ ships were used as platforms from which their crews launched heavy volleys of arrow and javelin fire at each other. Once the ships closed with each other, their crews continued the fight by boarding and hand to hand combat.

In later, medieval era armies, the bow was generally not considered a “noble” weapon. Men who were of lower social rank, and often too poor to afford the more expensive arms and armor with which the nobility were equipped, typically made up the archery elements of Medieval armies. Among Viking armies, however, even kings fought with bows. For example, at the great sea battle of Skold in 1000 AD, when Norwegian King Olav Trygvasson was cornered by his enemies and killed, during the long day’s battle King Olav fought mostly from the raised rear quarterdeck of his great warship the Long Serpent, alternately throwing spears and shooting arrows at his attackers.

In 1098 AD, a Viking fleet led by Norwegian King Magnus Barefoot was opposed, along the coast of Wales, by a Norman army. One of the Norman commanders, the Earl of Shrewsbury, rode down along the water’s edge to get a better look at the Viking fleet standing offshore. The Earl was — he believed — well protected by full mail armor and his shield. However, King Magnus and one of his warriors shot with their bows at his unprotected face. Though surely a long shot, given that they were shooting from a ship offshore, one arrow struck the nasal bar on the Earl’s helm and glanced off, but the other hit the Earl squarely in the eye and killed him.

Such long range, accurate shooting requires not only archers who are highly skilled, but also bows capable of striking hard at great distance — bows similar, no doubt, to the one hundred pound draw-weight yew longbow found at Hedeby. Numerous other accounts in the sagas suggest that such bows, and skilled archers to use them, were not rare among the Vikings. For example, an account of the Battle of Bravalla between Danish and Swedish Viking armies mentions shots by archers whose bows were so powerful their arrows pierced shields and helms, and various accounts of other battles describe arrows piercing shields and killing the warriors behind them. Archers were an important element of Viking armies, and exceptional deeds by archers — unusually powerful or accurate shots — were considered by the Vikings to be worthy of immortalizing in song and saga.

Heimskringla, or The Lives of the Norse Kings, Snorre Sturlason (Dover Publications, NY 1990; edited by Erling Monsen/trans. A.H. Smith)

Longbow: A Social and Military History, Robert Hardy (Bois D’Arc Press 1992)

The Great Warbow, Matthew Strickland and Robert Hardy (Sutton Publishing 2005)

The Saga of the Jomsvikings, trans. by Lee. M. Hollander (Univ. of Texas Press 1955)

The Viking Art of War, Paddy Griffith (Greenhill Books, London 1995)

Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga, edited William Fitzhugh and Elizabeth Ward (Smithsonian Institution Press 2000)

[1] For example, numerous items made of wood, including an entire Viking longship, were found in the Oseberg ship burial in Norway. The wood survived because the ship and all of the funerary gifts and other items it contained were enclosed in a burial mound of dense clay, which sealed the contents of the burial in an environment containing virtually no oxygen, thus preventing the normal decomposition process from occurring.

[2] The burial of grave goods, including weapons, with the deceased was tied to pagan Scandinavian beliefs about the afterlife. As the Viking peoples gradually converted to Christianity, the practice of burying grave goods with the dead ended — an unfortunate occurrence, from an archeological viewpoint.

[3] Some modern historians urge that Viking sagas be accorded little weight as sources of historical fact about the Vikings, for two reasons. First, some of the sagas contain stories or elements that are clearly myth or fantasy (such as the famous story of Sigurd and the dragon found in the Saga of the Volsungs). Second, although the sagas are believed to have been originally composed as a form of oral literature during the Viking Age, and at the time they were composed would have concerned contemporary events and persons of that period, or at least recent history, the written versions of the sagas that survive today date from a time well after the end of the Viking era — the oldest surviving copies of most sagas were written during the thirteenth century. Thus the danger exists that the sagas’ descriptions may more accurately reflect the time period when they were finally written down rather than the period they purport to describe.

The same arguments once were made about Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Both existed in only oral form for centuries, before finally being recorded in written form. Homer’s tales, like some of the Viking sagas, contain many elements of myth and fantasy. Historians long suggested that the ancient city of Troy, and the story related in the Illiad of its destruction by the Greeks, were merely fiction. However, archeological evidence continues to provide more and more evidence that Homer’s tales accurately describe not only grand events, such as the existence and destruction of Troy, but also even such small details as descriptions of styles of weapons and armor of the period. Those who doubt the accuracy of oral literary compositions perhaps fail to appreciate that societies with an oral literature tradition placed a high value on faithful renditions of familiar tales. Within a society with such an oral literature tradition, the mark of a skilled storyteller was his ability to accurately recite complex tales known to and loved by his listeners.

Many Viking sagas describe historical events that can be corroborated by other sources. Additionally, archeological evidence also has proved some of the sagas to be quite accurate. For example, for years the sagas which described the Viking discovery of North America were discounted by most historians as fiction. Those sagas are now known to be based on true events, however, for the ruins of what is without question a Viking settlement, similar in size and location to that described in the Vinland sagas, have since been found on the North Atlantic coast of Newfoundland.

[4] Heimskringla, or The Lives of the Norse Kings, by Snorre Sturlason (Dover Publications, NY 1990; edited by Erling Monsen/trans. A.H. Smith), page 454.

[5] Heimskringla, page 564.

[6] Heimskringla, page 98.

[7] The Normans were descendants of Vikings who had settled in western Frankia around the mouth of the Seine River during the preceding century. Although by 1066 the Normans had adopted the Frankish style of fighting as heavily armed and armored cavalry, there was still much of their Viking ancestors about them, including their heavy use of archers in their armies and their Viking longship-style ships in which their army invaded England.